The outbreak of pneumonia caused by the Wuhan coronavirus is ongoing in our world. More than half a million people have already been infected with the novel coronavirus, and 36,000+ have died because of it. Still, there are serious questions about almost any epidemic. Why do they (seemingly) occur more often? Why is there no universal medicine? And is it possible that they will infect the entire population of the Earth and doctors will not cope with them?

Read also: TOP 5 INCURABLE DISEASES THAT ARE WORSE THAN CANCER IN 2020

How do global epidemics like the COVID-19 occur?

Image by Aljazeera

A global epidemic is a disease that spreads not only within one city or country but around the world and affects millions of people. Mostly, we talk about infectious diseases but sometimes, diseases like Type 2 diabetes that associated with lifestyle are also as deadly as pneumonia. But the classical understanding of pandemics still implies that the disease can be transmitted from person to person or from animal to person by some kind of infectious virus.

Usually, viruses or bacteria act as an infectious agent, but scientists say they are just simple organisms. For example, although malaria has never become a pandemic, more than 400,000 people die of it in Africa and Asia every year.

Since the middle of the 20th century, dangerous diseases that have the potential to become a pandemic have indeed begun to appear more often. There are many reasons for this, and one of the most popular ones is the increased frequency of international travel.

One of the best and recent examples of it can be the history of an outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), when its pathogen virus (Covid-19) spread around the world in just a few days. The first sign of this outbreak occurred in 2002-2003. The first patient of SARS-2002 was a 64-year-old doctor from Chinese Guangdong, who arrived to attend a wedding in Hong Kong. He stayed there in a hotel and, without knowing it, infected 16 people. Later, the virus spread to Canada, Vietnam, and Singapore.

The second possible reason for the growing number of pandemics is the increased contact between people and animals, which occur because of the need to grow food for the growing population of the Earth. The infectious agent of the majority of pandemics initially occur in the animals and only then infect people.

In addition, climate change, deforestation, drainage of swamps and other anthropogenic activities are destroying the habitats of many animal carriers of potentially dangerous viruses for humans. Animals are forced to migrate, including to places inhabited by people. And considering that the population density is now higher than ever, the likelihood of transmission of an infectious agent from person to person has also increased manifold.

Why global epidemics do not kill half of the world’s population?

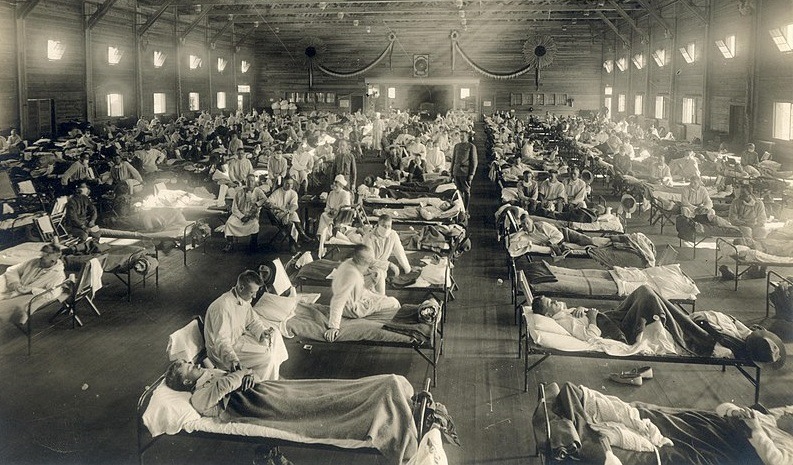

Large-scale pandemics have occurred more than once but, of course, half the world’s population did not die in them. Among the most deadly pandemic of all time, the Spanish flu in 1918-1920 killed at least 50 million people: about 3% of the world’s population at that time. In total, about 500 million got infected, i.e. 1/3rd of the world’s inhabitants.

Wikipedia

During an epidemic of the bubonic plague (also known as the black death), from 30 to 50% of the European population died in 1347-1351. It killed about 100 million people in the world, a quarter of the world’s population of that time. The plague of Justinian, which began in 542, probably took about 100 million lives.

There are several reasons why all these diseases did not destroy half of the world or even the whole humanity.

For example, people that often died from the plague had already been weakened by some other diseases (but the Spanish flu, on the contrary, killed primarily young people). Some people were completely resistant to infection due to the fact that their cells carried a special type of receptor, to which the virus clings worse, and today, their descendants are more resistant to HIV, which uses the same receptors to penetrate the cells.

Secondly, as sick people die, the percentage of individuals who are more resistant to the disease increases, reducing the chances of the virus spreading. A decrease in population density also contributes to this. Finally, although in earlier times, people did not know what exactly causes deadly diseases, they understood that it was necessary to isolate those who had already become infected and destroy the corpses. Such quarantine measures also very effectively stop the spread of the disease.

Another reason that fatal diseases did not kill all people is, in fact, the mortality of these diseases. If the virus kills almost all the infected, they do not have time to pass it on to other people, and the distribution chain breaks. It is possible that something like this happened during numerous epidemics of the Ebola virus, the mortality rate of some strains of which reached 90%.

Why do all pandemics today start somewhere in Africa or Asia? Are they developing biological weapons?

Hypotheses that viruses of deadly diseases are created artificially in top-secret laboratories appear stably after the discovery of each such microorganism. However, modern molecular biological and virological studies clearly show that external intervention is not necessary: viruses and bacteria mutilate or mix their genome with the genome of other organisms as they pass into them, for example, different strains of the influenza virus. Analysis of the genomes of new viruses allows scientists to accurately determine which animal it come from and how exactly the changes occurred that made them dangerous to humans.

Moreover, in fact, Africa and many Asian regions are not the main places for the emergence of new dangerous diseases: many times they had appeared in the high latitude regions. Another reason is poorly established healthcare systems (including constant military conflicts), poverty, inaccessibility of hospitals, close contact with animals, no regular doctor-checkups and often high population density.

Is it possible to predict where a new dangerous virus will appear?

In some cases, yes. The most striking example is the flu. Seasonal epidemics are caused each year by different strains of the virus, and in order to produce effective vaccines, more than a hundred national influenza centers at WHO monitor which genetic variant circulates in the population between epidemic peaks.

The laboratories send the data to the staff of five research centers, after studying all the available information and consulting with local experts on the basis of complex models that describe the changes in the genetic variants, decide which variant is most likely to cause an epidemic in the coming year. Sometimes, scientists make mistakes, but this does not happen so often, and on average, the effectiveness of influenza vaccines

Even after the predictions of the new and unexplored virus, the situation is worse. Health systems do not have enough data to make any reasonable predictions. According to some estimates, only 1.67 million viruses circulate among mammals and birds, and from 600,000 to 800,000 of them could spread to humans.

Nir Elias/Reuters/Landov

Therefore, the main efforts are now aimed at minimizing the consequences of already appeared viruses. Nevertheless, in 2009, the Global Virome Project was launched, the purpose of which is to find and characterize a significant part of such potentially dangerous viruses.

It was planned that the creation of such a database would take 10 years and cost at least $1.2 billion. However, so far, the project has not brought significant results, and many researchers doubt its feasibility, believing that it would be much more efficient to invest in constant monitoring of regions in which the risk of the emergence and spread of new viruses is maximum.

The reasons for skepticism are the inability to build informed predictions only on the basis of data on the genomes of viruses. High-level laboratory studies are needed to make accurate forecasts, but such events for 800,000 viruses will cost a huge amount of money.

Is it possible to understand how dangerous a new disease is at its initial stage?

It is possible only if the country has well-established systems for monitoring the epidemic situation and early detection of potentially dangerous diseases. In addition, in order to adequately assess how dangerous a new disease is, consultations with specialists from other countries and large international organizations are often necessary.

Unfortunately, this often does not happen, since the countries in which a new virus appears and begins to spread often try to hide the true state of affairs in order not to provoke negative consequences for the economy, such as restrictions on flights and trade.

Why is it so difficult to create a vaccine due to the virus mutations as bacteria also mutate but antibiotics still work?

Bacteria mutate noticeably slower than viruses (on average, 10-10,000 times). In addition, viruses multiply much faster, so the final level of changes in their genome is even higher. For example, HIV can produce 10¹⁰ virus particles per day. Such swiftness makes the creation of vaccine economically disadvantageous because they have to be constantly updated. To avoid this, many antiviral drugs use several active substances at once, aimed at different systems important for the virus.

In addition, the virus spends most of its life inside the host cell and uses its enzyme system, which means that killing it also requires killing the cell. Therefore, many antiviral drugs are characterized by very pronounced side effects. Bacteria can be killed regardless of the cells of the host organism, and the same antibiotic often works for a large group of microorganisms, as it affects some key mechanisms for their life.

Viruses are characterized by much greater biodiversity, so often drugs are created individually. For example, antiretroviral drugs cope very well with HIV as they are designed to fight, but they are useless when infected with any other viruses whose life cycle differs from HIV. Vaccines that prevent infection and do not fight against an infection that has already happened, remain a much more effective remedy against viruses.

As there is no vaccine for the coronavirus, does it mean an epidemic like the Spanish flu may happen again?

There is an established mechanism for creating effective vaccines just for influenza. Although for some strains, it is harder to create them than on average. But epidemics can be stopped even without vaccines due to well-established emergency response systems, quarantine, and isolation of patients. And although it cannot be ruled out that a virus similar in danger will reappear, from the beginning of the 20th century, the health systems of most states have improved significantly, so one can hope for a relatively quick stopping of the spread of such a virus.

How to protect yourself? Will stopping communication with people from the infected regions and wearing a mask help?

A universal strategy that completely protects against infection does not exist. In the case of each infection, there are nuances.

In general, for infections transmitted from person to person by airborne droplets, standard hygienic recommendations work well, so wash your hands more often and do not touch your face (many viruses persist for a long time on various surfaces and easily penetrate the body through mucous membranes). It makes sense to avoid crowded public places, try not to contact people who have obvious signs of the disease.

If you really want to, you can wear a surgical mask: some studies show that it is no less effective than a respirator, but it is important to do this constantly. If you periodically take off the mask to breathe and do not wash your hands, there will be no protective effect.

Are there any plans to save people if the epidemic really threatens humanity?

Many developed countries have strategies, dealing with large-scale epidemics. However, given the radically increased level of communication between countries, measures taken only within one region are likely to be ineffective. Therefore, WHO insists on the need to notify the international community of outbreaks of potentially dangerous diseases as early as possible, which, as already mentioned, does not always happen, and to establish an exchange of experience and coordination between developed countries that have resources for effective intervention, which is also not effective enough.

According to an article published on PubMed Central®, in order to stop the spread of dangerous infections, it is necessary to take very strict measures. For example, introduce quarantine or kill animals carrying the virus. For obvious reasons, the locals do not like this, and they often try to break the rules that they consider too harsh. It is believed that such behavior led to the fact that the outbreak of Ebola in 2014-2015 could not be stopped quickly, and the disease managed to spread widely.

This is certainly what the WHO and WEF want us to believe. They are certainly keen on infecting all the the people on Earth with the experimental vaccines.

Great article

Sad